‘After a few marches to Minsk and Kalushin, our division took up a position near Zhukov in a lovely oak grove, which of course quickly disappeared as campfires were built for boiling up food. It was the end of April, the days were hot, the nights quite cold and towards morning there was frost. There was cholera among the troops.’ From the memoirs of Gregory Ivanovich Philipson, Russian Archive 1883. Volume 5. p. 126.

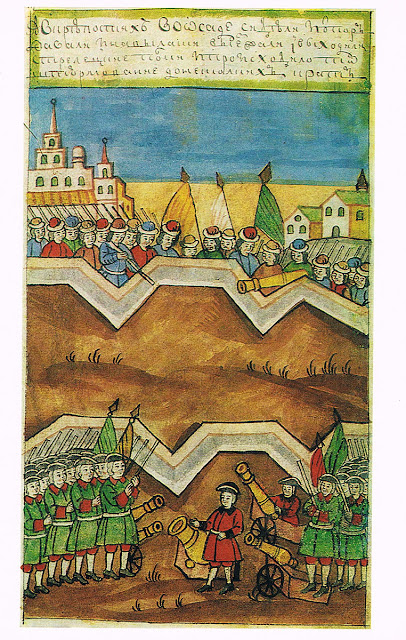

These words come from the amusing and colourful reminiscences of Grigory Ivanovich Philipson, later General Philipson, who as a young man served as a Lieutenant in the Duke of Wurttemberg Regiment of Grenadiers during the Polish Uprising (1830-31). Philipson’s writings, the memoirs of other soldiers, and regimental histories often present vivid pictures of military life on campaign. As in Ukraine today, ecological devastation, disease, bad weather, procurement difficulties and plunder featured regularly and combined to frustrate the intentions of those in command.

Unseasonal weather was a constant problem. The Polish campaign started in December 1830, when it was expected to be cold and the countryside frozen. Nature however did not oblige and, in addition to the expected frost and snow storms, the troops marching into Poland were often hindered by thaws, melting the rivers along which they hoped to travel, making the roads and impassable and seriously slowing progress. As late as May, inclement weather was a problem. Major General Berg of the General Staff wrote to Field Marshall Diebitsch: ‘The men are moving well, but not the horses. It’s hardly possible to drag the guns and carts along the terrible roads.’ Even in June Philipson notes: ‘The next march… was notable due to our state of exhaustion. We did not walk, but crawled through sticky mud and forests, only travelling 10 versts (a little less than 10 kilometres) in one day.’

Feeding the troops was also a problem. The Russians entered Poland from a number of locations and rapidly ran into supply issues. This led to forced requisition, looting and theft which turned the initially passive Polish peasantry into enemies. Philipson describes how he saw ‘whole villages completely plundered and the inhabitants ejected. In some a few half-starved people remained, and with a hopeless indifference they looked on as their last crust of bread was taken.’ Later he comments: ‘Those amongst us who thought that it would be an easy war had to think again….the Polish forces defended to the last man, forcing us everywhere to think differently about the Pole, forgetting about them being nephews and eternal brothers.’

Stark parallels can clearly be drawn between that Russian adventure and the current tragic and pointless war in Ukraine. Of course, contemporary warfare is a very different thing from that waged in the early 19th Century, but some features never change.

I am currently researching the Polish Uprising of 1830/31 to support the creation of my current work in progress (working title: The Prince’s Legacy.) The prequel, ‘Small Acts of Kindness, a tale of the first Russian Revolution) is currently enduring its final edit and will be published by Unicorn later in 2022