We are now moving deeper into December, and it is dark a little after 4 p.m.

It was a little earlier, just after 3 p.m. in St Petersburg on December 14th 1825(Old Style) when Nicholas Pavlovich, newly created Emperor of Russia, ordered guns to be fired to scatter 3000 rebel troops. The soldiers had stood in Senate Square for hours refusing to swear the oath of allegiance. The men, assisted by a few radical civilians, were purporting to support his older brother, Grand Duke Constantine, who had formally renounced the throne. However this was just a pretext; following the death of their older brother, the Emperor Alexander the First, some three weeks earlier many of the troops were not really interested in supporting either brother. Their true aim was to bring an end to the autocratic system, to create a republic or a limited monarchy, and to free the millions of serfs owned by the nobility at the time.

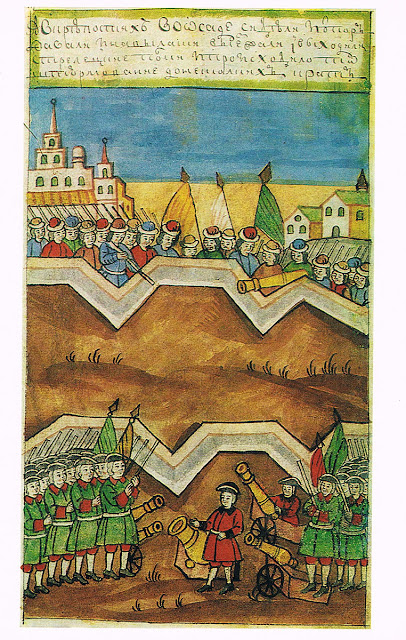

Nicholas decided to act as night fell, apparently afraid that supporters of the uprising among ostensibly loyal regiments would take advantage of approaching darkness to join the rebels. He first tried to scatter the men by using blanks, but then, when this failed, used real ordnance. The ranks of soldiers scattered, some fleeing to form up on the frozen Neva, where they were pounded with cannon until the ice broke. And so ended the rebellion that was subsequently known as the Decembrist uprising, an event that many have also designated the first Russian revolution.

The events that took place in December one hundred and ninety seven years ago, in Saint Petersburg, form the pivot of my novel, Small Acts of Kindness, a tale of the first Russian revolution. The book was published two weeks ago by Unicorn Publishing, under their Universe imprint. It has been described by one critic as an accessible way into a little known period of Russian History, and if you want to learn more about the incident, and its aftermath, while enjoying a tale of romance, adventure and redemption, you could do worse than purchase a copy, preferably from your local bookshop. Alternatively a Kindle version is available on Amazon.